On my morning walk today I was reflecting on a book I just started called, Wild New World by Dan Flores, which tells the story of the rise and fall of animals in North America over the last few million years. (Who knew that camels are originally from North America!?) In the book, Flores posited an interesting question and a source of discussion amongst scientists: when did the Anthropocene (i.e. human-shaped) period begin? My immediate and confident answer, as it turns out like many others, was the Industrial Revolution, which turbo-charged human effects on the planet in so many ways, from resource-depletion to pollution to population increase on a, well, industrial scale.

But a number of scientists have put forth a different viewpoint which I have now bought into: that the Anthropocene period began once people started farming and herding. Essentially once we stopped being just another animal and instead started thinking of all the other animals and the planet as resources of ours to harvest and use, we began a journey that has taken us where we are now.

Which, of course made me think of Boeing.

I was the seventh of seven children. (Although my mother always said, with a hint of seriousness, that if I’d been the first, I’d have been the last…) I remember quite distinctly that in my mum’s eyes, if I had become a doctor or an airline pilot, that would have been the zenith of her hopes for me, with airline pilot being at the very top of the heap. That idea came from another era, not the post-deregulation era where pilots have slowly been crushed toward being air-Uber-drivers in the respect department. (Not meaning to demean Uber drivers, but “gig economy” means “you are an easily replaceable cog.”) Anyway, in the golden age of air-travel, one name stood above all others: Boeing. Frankly, it sat alongside IBM, Bell and a few others as the crown jewels of American industry. And it is worth noting that for most of Boeing’s existence, the CEO was paid handsomely, but not obscenely, the workers were well-paid – and unionized since 1935. The planes were the pride of the skies, pushing the boundaries of travel and luxury.

And safety.

But a funny thing has happened in the millenniums since humans became resource-creators: we have also become resource-hogs. Slowly, over-time, it has become a competition for who can control, build and use resources the most. This was done relatively benignly for thousands of years (although don’t ask the passenger pigeons or indigenous people-groups) until the mid-1970s, when a theory gained fashionable prominence that shareholder value was the only metric that mattered. That set a fire on Wall Street, (and a relaxation of safeguards put in place after 1929). Unfortunately, that fire led to crashes in 1987, 1999, 2008 and 2020 – one per decade.

In 1997, in a breathtaking sleight-of hand, giant Boeing bought small and struggling McDonnell-Douglass, maker of the infamous MD-80 airliner (“It’s cramped and old, but at least it’s noisy.”) Yet when the dust cleared, the management of McDonnell-Douglass were running the new company with McDonnell CEO Harry Stonecipher in charge. With a CEO that prized profitability over engineering and a chairman with zero aviation background, the culture-change was neck-snapping. The corporate headquarters was quicky moved away from Seattle to Chicago, making it so much easier to ignore feedback from the senior engineers – whose ranks were soon thinned anyway. Production began to be moved to “Right to Work” states where union decimation was baked into the DNA.

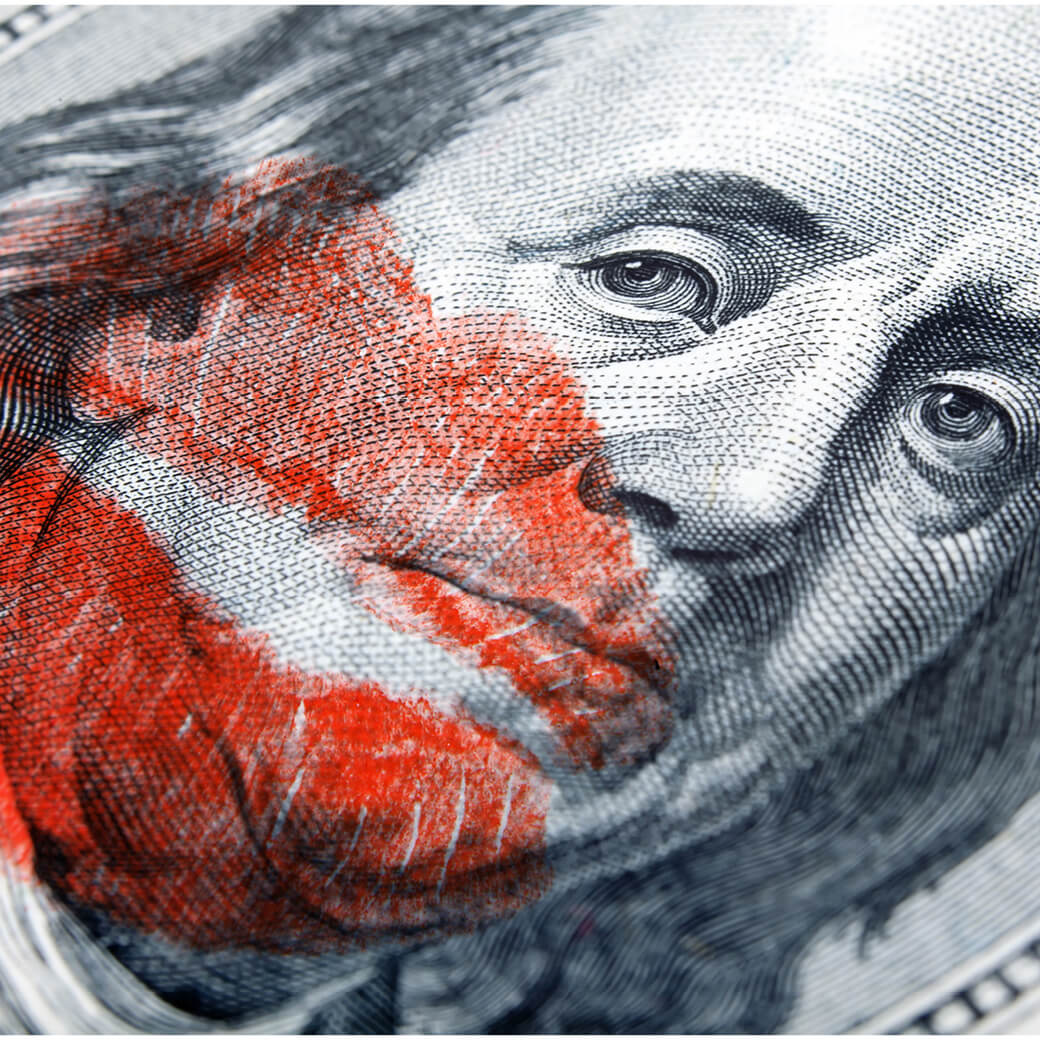

And here we are a short couple of decades later with this jewel of American industry in tatters. Boeing savagely streamlined its production safeguards, weeded-out much of the senior (i.e. costly) engineers, crushed the unions, but did manage to obscenely reward senior management and give $59 billion to shareholders in just the last decade. (With Stonecipher being the second largest shareholder).

Previously, I would choose to fly on routes that used Boeing equipment, to both fly the flag and because I trusted the plane. Now I have a flight to Atlanta coming up and I chose the route based on it being Airbus for all 4 legs. I am confident that I am not alone in this choice.

What’s going on at Boeing is an alarm bell for what is going on throughout our nation. We’ve traded jobs and pensions for many, for billionaire status for a few but kept the name capitalism to quell protest. That $59 billion (or just an equitable portion of it) could have paid for a lot of safety protocols – and used to.

Which brings me to a hot-button word: Equity.

Equity is a word that lives in two almost diametrically opposed definitions. In one definition, it stands for fairness and impartiality, in the other, it stands for how much of something you own. Could any word be more tied up in the dichotomy of human existence? As a friend of mine once wisely said, “In the US, it’s expensive to be poor.” That is very true, not just in the monetary sense that the poor are subject to higher APRs and cannot afford to buy in bulk or, increasingly, afford shelter, but also that poor people are more likely to be affected by violence and sub-standard healthcare. And guess which group always has the petroleum refinery built close-by their neighborhood….

Sadly, increasingly, the US and much of the world has become a winner-take-all economy. The pursuit of more instead of enough has become the most human trait.

I recently listened to the ex-mayor of Stockton CA, Michael Tubbs, talk on a wonderful podcast called Dreaming in Color. He talked about the “myth of exceptionalism” and also about numerous very successful pilot programs replacing food stamps and housing subsidies with just giving people money, shining harsh light on the myth that poor people cannot take responsibility for their own lives. – The truth being much more aligned with them as just on the losing side in the winner-take-all economy. The travails at Boeing show that more and more of us are losing via the same playbook. With the seismic wealth disparity that is becoming the hallmark of modern US, “poor” is perhaps better replaced by “not wealthy” (or, maybe, “powerless”) as an indicator of the demarcation between living in comfort and living with concern. As a by-product of this metamorphosis, anger is increasing proportionally, populism is attractive and people are looking for someone to blame – sadly their focus is generally on others with similar struggles that they are encouraged to see as enemies.

The entire world economy has become based on you regularly throwing away what you have and replacing it with something new. If you total up the real cost of doing that, in money, in relationships, in families, in mental health, it is a sad tale told too often.

The love of money is cancerous enough to get a prime mention in the Bible. The breakdown of the family unit (which, it is important to point out as proven world-wide for millenniums, does not require marriage or heterosexuality) has led to the proliferation of homelessness and poverty. And in the last 20 years the internet and social media has led to even “friends” being a transactional, competitive resource item.

Not so long ago, friends, family and community were low cost and high value. Now, for too many, they are a shrinking asset and that is the highest cost of all, personally and societally.

What’s most important for you, a society where a few can rise to the height of gods or one where no-one can fall too far? One where success is only based on how well you do or how well those around you do, also? Do you look for a rising tide to lift all boats or a tsunami on which a few surf over the scurrying’s of everyone else?

Under which auspices do you want the plane built that you and your loved ones will next fly on?

“Everybody does it” may be the most dangerous moral shortcut we’ve collectively agreed to tolerate.

When humans face true cataclysm, we pull together. When it’s about money and power, not so much.

People seek to have power over their own lives. Teens, adults, older adults – everyone. What happens when they feel powerless? What happens when you or your communications make them feel they have less power?

The way we talk to others demand that they accept an identity for themselves, and sets up a particular relational dynamic. If we're not careful, that identity can be stigmatizing or turn away the very people we're trying to help.

Get the latest posts and updates delivered to your inbox.