Usually when talking about The Relational Intersect, I say that the problem in interpersonal relationships is not “what I think about you and what you think about me” but in “what I think you think about me and what you think I think about you.” We react to what we imagine is in the other person’s mind, usually based on our own life experiences and what we might think or say under similar circumstances.

Which led me to thinking about intellectual property and capital punishment.

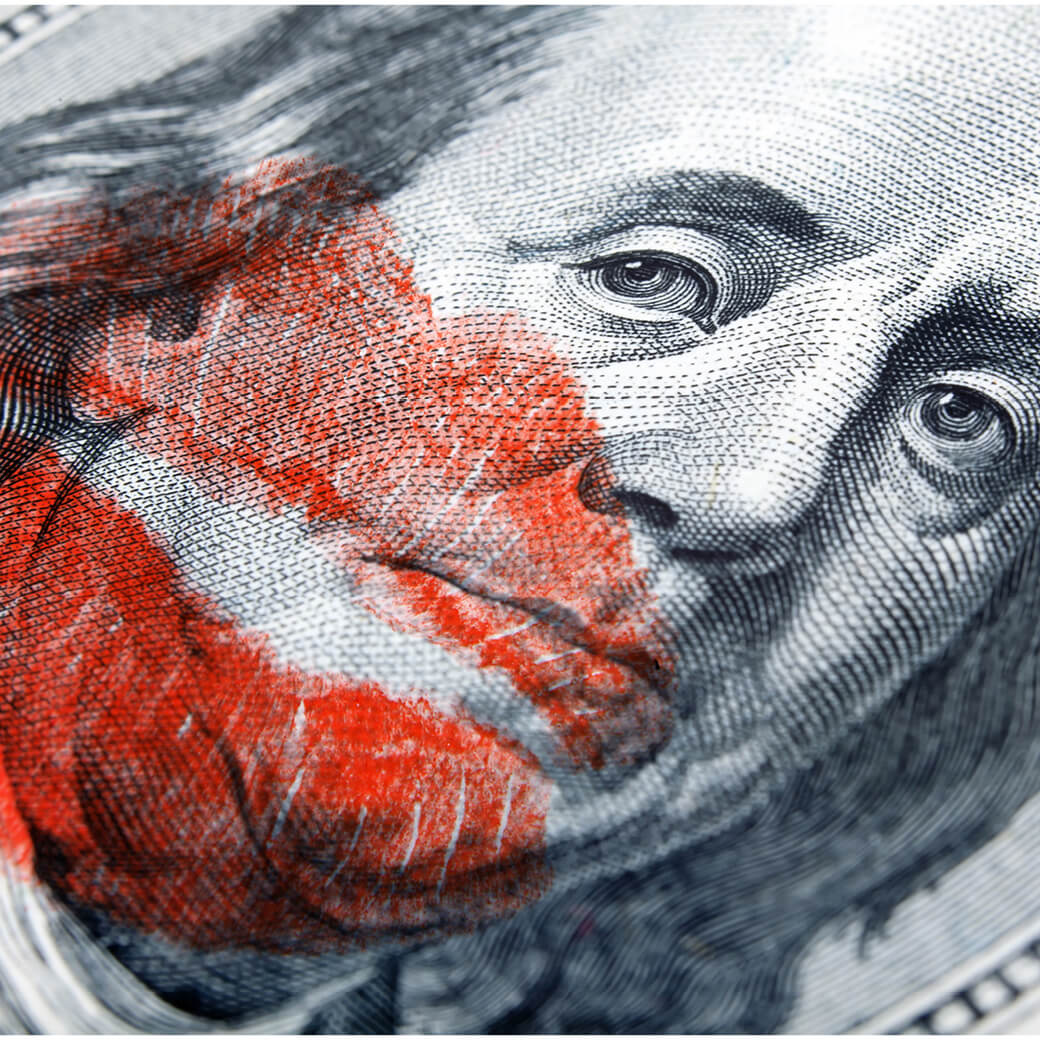

A long-time thorn in the relationship between the U.S. and China has been over intellectual property issues: patents, trademarks, etc. People in the US tend to see China as a nation that has little respect for intellectual property laws and we castigate China as fomenting and rewarding “thievery” around these issues.

The truth is more complex. China’s history gives them a different viewpoint. It’s worth noting at this point that China has written history going back over 3,000 years, so they’ve had a bit of time to develop some social constructs. The one I want to point out here is that there is a long history of a more Confucian, paternalistic society in China where, amongst other things, one is encouraged to be loyal and diligent towards one’s superiors, and that the greater good is always more important than any individual.

Compare this to the U.S., where we like to see ourselves as rugged individualists, living by our cunning and can-do and where each person is responsible for pulling up our own bootstraps.

Little of either is universally true, but because it is how we like to imagine our national identities, it then makes us liable to act and think in certain ways and, just as importantly, makes us liable to interpret other people’s actions through the prism of our own imagined identity.

By the Chinese way of thinking, the idea that you would make a discovery and that the discovery would then belong only to you is ludicrous. What about the community that supported you and your family? What about the schoolteachers and professors that expanded your mind? What about the nation that created the university? In their view, your discovery did not appear from some intellectual thermos flask, insulated from outside influence; you are who you are because of others and your discovery, in some way, belongs to them also.

In the U.S. we believe in, “I stuck a flag in it, therefore it’s mine.” That version of ourselves goes back to (and beyond) the homesteaders racing across the plains of Montana to plant flags in the land to claim and till it as their own. (Land, it is worth remembering, that was already in use and had been for thousands of years, but by a culture that did not subscribe to our norms of “owning” land.)

So who’s thinking is correct? That, of course, is in the eye of the beholder. It certainly is important to remember that there are often other ways to do things than that which we may be conditioned to think of as the “proper way” and which may have just as much claim to legitimacy. Which is not to give China a free pass at the WTO, but it is to say that Western IP laws are incongruent with how Chinese society has worked for thousands of years. As with all things between people or nations, it is easy to assign evil or criminalistic intent because we only view it from the point of what would be in our own minds or hearts if we acted in the same manner.

Something I have been mulling and researching of late is the fact that China executes more people than any other nation on Earth. And, of course, the US has a rather complex relationship with capital punishment.

But this is a case where the different national identities mentioned above lead societies to similar results for different reasons.

In the US, our “rugged individualism” leads us to largely make people solely responsible for their actions. “He murdered him and now he should die. It is ‘his’ responsibility.” It’s worth taking a moment to compare this also with traditional Native American Indian culture that would have found such a logic-string blindingly unsound. They would consider it a fault with the family of the person who committed the act and of the wider society that one person killed another. Why did “we” not stop this? How did “we” fail these people? Why did “we” not step in when we saw these potential problems on the horizon? The families concerned or the whole community would come together to find restitution. Certainly, no one would be executed.

In China it is more pragmatic. By the same logic that leads them to a different view on intellectual property, it is the greater good for society that is sought. If you are a killer, you need to be removed. Same for drug dealers. If you are creating dissonance in society, then you will be removed from society. Very often via execution.

Two very different nations that sit on very different societal structures, but if you look at the executions, you might get the impression that they think the same way. Not so. The same lack of dissonance that may seem attractive in China would be viewed as a suffocating lack of self-determination in the US. In the same way, the far ends of personal freedom believed a birthright in the US might look like puerile selfish narcissism in China.

Here, I am speaking of two nations, but the same kind of rules apply to people. Humans are extremely complicated and spend their first 20+ years of their lives being shaped by experience and parental influence and some people’s childhood experiences are hauntingly negative and wildly deviate from normal societal mores and such experiences leave lasting effects. Just because you agree on one action or one display of emotion, does not mean that you got there via the same route. And the obverse is just as true; Just because you see any one thing very differently does not mean that the other person does not have valid or at least imprinted viewpoints for their decisions and opinions.

Furthermore, people live to their definition of their identity. Where one person may see themselves as adopting characteristics that are strong and upright, another may observe those same characteristics as weak and fragile.

If we can stop viewing other people’s actions only through the lens of our own beliefs and experiences and instead look at their path to their beliefs and concomitant actions, we will create a space for meaningful and respectful conversations. And, if we are all open to change or at least understanding, we might be able to find some valuable common ground and perhaps some better and more fruitful ways of living life together.

Considering all the challenges our cities, country and world faces, I am reminded of Benjamin Franklin’s quote: “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we will all hang separately.”

That begins with the desire to understand each other and resisting the urge to ascribe ill intent to those people who live their life differently than we do.

“Everybody does it” may be the most dangerous moral shortcut we’ve collectively agreed to tolerate.

When humans face true cataclysm, we pull together. When it’s about money and power, not so much.

People seek to have power over their own lives. Teens, adults, older adults – everyone. What happens when they feel powerless? What happens when you or your communications make them feel they have less power?

The way we talk to others demand that they accept an identity for themselves, and sets up a particular relational dynamic. If we're not careful, that identity can be stigmatizing or turn away the very people we're trying to help.

Get the latest posts and updates delivered to your inbox.