I love NFL football. I also hate it.

Watching it used to be a fairly simple affair – if you had cable TV you just turned it to the network it was airing on. But in the years since the rise of the streaming channels, the NFL has gotten ever more fractionated. To wit: you can buy the Sunday Ticket from YouTube that will deliver you every game played on Sunday. Buuuut then there is the Thursday night game available only on Prime TV. And Monday Night Football only on ABC and/or ESPN “Ultimate” (which, of course involves an up-charge.) Thanksgiving games are old-school inasmuch as they air on CBS, Fox and NBC, but Christmas has been sold to Netflix, so you need that to watch then. As a fan, I feel milked. ESPN Ultimate, for me, was the final straw. I did not upgrade; I cancelled the package I already had instead.

I know where your mind is going: The Roman Empire.

Rome started out as a Republic, from which ideals it amassed massive wealth and a flowering of innovation, arts and culture that we still salute and emulate to this day.

And then greed took over. Wealth became concentrated. Dictatorship replaced democracy (as it was) Over time, the life of the average Roman citizen became ever more difficult. The provinces were ever more squeezed. Rome’s ability to throw its power around became hollowed out. For a while, “Bread and Circuses” took the masses’ attention away from the issues, but irreversible decline set in and finally the unthinkable happened, the barbarians were at the gate and did not knock politely.

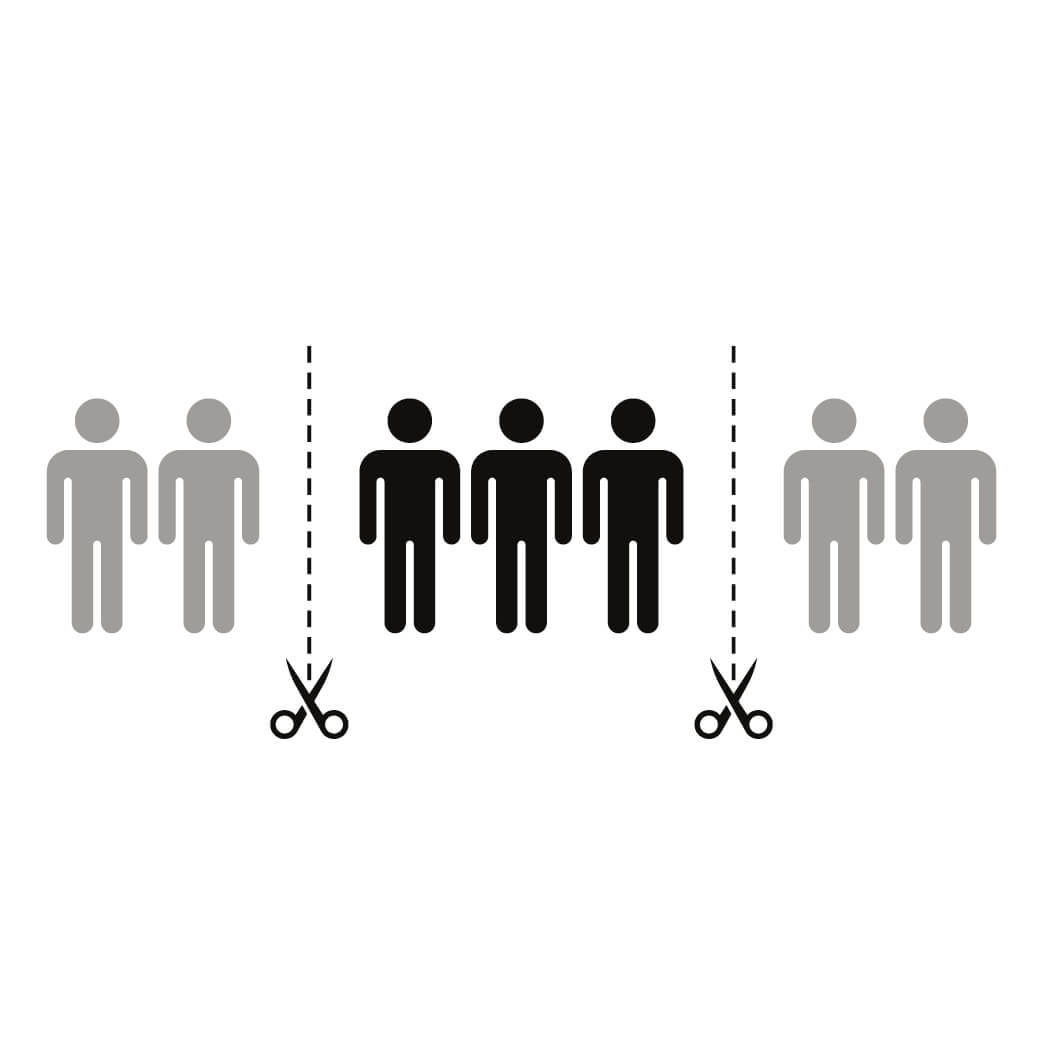

This “greed cycle” has repeated itself over and over throughout history. A spark of innovation that leads to growth and dispersal of wealth throughout the strata of the collective (usually a country, but Rome and Venice were city-states), then consolidation of wealth and power to a hyper-wealthy ruling-class, followed by depression and oppression of those without power and wealth and then some form of collapse via revolution, war or just economic flame-out.

Thus went the British Empire that surfed on the tsunami of the industrial revolution to a world-wide empire, but lost most of everything through greed, oppression, financial crashes and war.

The Mongol Empire had, for its time, startling innovation in mobility and military strategy. The Dutch Golden Age and Empire. The Spanish Empire. The Russian Empire. – All followed similar arcs: born via innovation, dying via extraction. An arc as follows:

In each of the examples mentioned above, there was a lot of suffering, and few were spared it.

When we wonder where all the rage that feels ever more a part of our culture in the US is coming from, it is worth pondering where our nation is on that arc and how that might affect the populace. The NFL feels like a microcosm. It has grown rapidly into the biggest and most popular sport in the US. Now it is in the extraction phase where fan experience has taken a back seat to revenue optimization. The average cost for a family of four to take in one NFL game at the stadium stands at $777.89. The NFL Sunday Ticket on YouTube is $480.

Similarly with airlines. Once flying was an aspirational treat, a highlight of a journey. Now the experience approximates a dirty, broken-down taxi ride with a surly cabbie. Not blaming the cabin crew for this; the dynamic revenue optimization of airlines means that on a list of ten priorities, the coach passenger experience comes eleventh.

As I have written before, in the version of capitalism that existed in America post WWII and before 1980 (during a period that many people consider the apex of US economic, cultural and geopolitical power), workers were considered an investment, to be nurtured and respected as partners in an often career-spanning, symbiotic relationship with company owners. Unions were large and the average worker could take care of their family and retire with a pension. This was under both Republican and Democratic party primacy, and as such was simply The American Way of Life. Since the late 1970s capitalism dramatically shifted priorities to reflect the Friedman Doctrine – that shareholder return is a company’s only responsibility. At which point, workers also shifted from being an investment to a commodity and, resultantly, the lower the cost burden they could represent, the better it was considered to be. Fifty years of off-shoring and pay-cutting later, here we are.

And it is not just about employees. While drug companies like Pfizer and Merck claim that they need to charge exorbitant prices for drugs in order to fund research, the numbers tell a different story. Between 2008 and 2017 those 2 companies spent $590 Billion on stock buybacks and dividends - more than 100% of their profits - thus highly rewarding the stock owning company officers and leaving little for research and innovation. (BMJ, 2019)

When Steve Jobs died, I wrote an essay positing that we would get to find out if Apple is a great company or if Steve Jobs was a great man. In the years since, Apple has spent close to $900 Billion on stock buybacks and dividends while spending less than 20% of that on innovation and product development. Analysts from Harvard Business Review and Bloomberg have warned that this pattern—shareholder enrichment at the expense of reinvestment—has left Apple behind rivals on critical fronts like AI.

But this essay is not about that…exactly.

It is about all the people on the wrong side of these equations – which is most of the people in the US. When we see anger and blame in our politics, depression and substance use in our homes, suicide in our families and violent confrontation on our streets, it is worth asking why and what we can do about it. Most assuredly, the answer is not to be found in more anger and more partisan finger-pointing.

It has been well proven that absent other forces, when humans face an encompassing disaster, like an earthquake or cataclysm of some sort, they naturally bond together and come to each other’s aid. It was seen in the London Blitz, after 9/11 and in Hurricane Katrina (erroneous reporting aside). In the great 1965 Northeast Blackout, thirty million people in nine states lost power. Yet it was heralded as a time of great community coalescence. New York City registered the lowest amount of crime on any night of the city’s history since records were kept.

But what if the cataclysm is not encompassing? What if it only affects some, or others are blamed for it? Well, 1930s Germany is only how far we need to look to answer that question.

It might be that the majority of people in the US right now have a sense of dread and depression and a feeling that they are losing ground. As has happened in other times and places, it is tempting to blame “others” or “the other side” and view them or their beliefs as an existential threat. People from other parties. People from other countries. People from other lifestyles. Who amongst us would not go to the mat protecting those we love? It follows that positioning a person’s difficulties as due to the beliefs and actions of “others” becomes a very powerful lever for those that might wield it toward their own benefit and others loss. - This is true on all sides of the political arena.

History is only clear to historians. And even then, only some of the time. For the people living through it, it is impossible to really know if you are in the springtime or the autumn of a civilization. Almost no one foresaw the crash of 1929 or 2008 (a few famously predicted it, but they could not truly know). The Romans in the 4th century thought they were in a rough patch. The 1930s depression, at first, was seen as a temporary downturn.

So, all we really get to control are the little parts of our own existence that we do have control over. How are we going to treat each other? How are we going to think about those that do not share our opinions? During the period when America was at its greatest, we made the greatest strides in taking care of the populace, in health, in retirement, in civil rights, in representation.

Which is to say, Americans made the most gold when we followed the golden rule. What an inspiring thought: when we treat each other well, we make the most money. It’s an already-proven nation-building pay for performance plan.

History will let us know for sure, but it is not difficult to see our current time as closing in on an inflection point. We still can restore and rejuvenate the dream that is America. But it won’t happen if we imagine that course-correction is something we demand only of others. Renewal requires all of us.

I remember the reliably kookie NFL coach Gerry Glanville once saying to a new referee that he accused of throwing a bad flag, “This is the NFL —which stands for Not For Long when you make them calls.” The US also might be in a “Not For Long” period with a choice looming large. Will we make the commitment to step back onto the path of community – or continue the march toward catastrophe?

When people see public health messages directed at them, they are very aware that others can see them also and it can trigger concern of how other people in the community now think about them.

People don’t change by rejecting their identity – they change by finding new ways to stay true to it.

People seek to have power over their own lives. Teens, adults, older adults – everyone. What happens when they feel powerless? What happens when you or your communications make them feel they have less power?

The way we talk to others demand that they accept an identity for themselves, and sets up a particular relational dynamic. If we're not careful, that identity can be stigmatizing or turn away the very people we're trying to help.

Get the latest posts and updates delivered to your inbox.